Introduction to Rigid Transformations

By Bolun Dai | Apr 20th 2022

In this blog, I want to talk give a review of rigid transformations, in specific rotation and translation. Although this is the most basic concept in robotics, I tend to confuse many concepts. Therefore, this to me is more like a cheatsheet. The content is developed from

Rigid Transformations

A rigid transformation in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) is a mapping \(g:\mathbb{R}^3\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^3\) that has the following properties:

- Length is preserved \(\|g(p) - g(q)\| = \|p - q\|\) for all points \(p, q\in\mathbb{R}^3\).

- The cross product is preserved \(g_*(v\times w) = g_*(v)\times g_*(w)\) for all vectors \(v, w\in\mathbb{R}^3\).

In addition to the above properties we can also prove that the inner product is preserved \(v_1^Tv_2 = g_*(v_1)^Tg_*(v_2).\)

We can see from the above animation, that after translation and rotation the length of the two blue lines did not change (\(\|\cdot\|\) did not change), thus satisfying the first property. From the definition of inner product we have

\[\langle \mathbf{a}, \mathbf{b}\rangle = \|\mathbf{a}\|\|\mathbf{b}\|\cos(\theta)\]where \(\theta\) is the angle between \(\mathbf{a}\) and \(\mathbf{b}\). We can see that the angle between the two lines did not change (\(\cos(\theta)\) does not change), and since the length is also kept the same, the inner product is preserved. The rotation is in a 2D plane, but we can see that for the body coordinate system before and after the transformation (orange axes) the z-axis is the same, thus the cross product is preserved. This result generalizes to 3D rotations.

Rotations

Properites

The rotation matrix has the following properties \(SO(3) = \{R\in\mathbb{R}^{3\times3}\ |\ RR^T = I, \mathrm{det}R = 1\},\)

where \(SO(3)\) represents the special orthogonal group. Since the rotation matrix is a group under matrix multiplication it has some additional properties:

- Closure: If \(R_1, R_2\) are rotation matrices then \(R_1R_2\) is also a rotation matrix.

- Identity: The identity matrix is the identity element.

- Inverse: Each rotation matrix has an inverse \(R^{-1} = R^T\).

- Associativity: For rotation matrices \(R_1, R_2\) and \(R_3\) we have \((R_1R_2)R_3 = R_1(R_2R_3)\).

Also rotation matrix is a rigid transformation which means that

- R preserves length: \(\|Rq - Rp\| = \|p - q\|\) for all points \(p, q\in\mathbb{R}^3\).

- R preserves orientation: \(R(v\times w) = (Rv)\times(Rw)\) for all vectors \(v, w\in\mathbb{R}^3\).

Representations

We can see from the animation, that if we have a vector \(\mathbf{q}\) rotating with respect to another vector \(\omega\) with constant angular velocity \(\|\omega\|\), its linear velocity can be calculated as \(\dot{\mathbf{q}} = \omega\times\mathbf{q} = \hat{\omega}\mathbf{q}\). From the knowledge of linear systems (solution of \(\dot{x} = Ax\) is \(x(t) = e^{At}x_0\)) we have the trajectory of the vector as \(\mathbf{q}^\prime = \mathbf{q}(t) = e^{\hat{\omega}t}\mathbf{q}_0\). Additionally, if we have \(\|\omega\| = 1\), then we have \(t = \theta\) the rotation angle.

From Euler’s theorem we know that for any rotation matrix \(R\in SO(3)\), it can be seen to be equivalent to rotation about a fixed axis \(\omega\in\mathbb{R}^3\) through an angle \(\theta\in[0, 2\pi]\). To represent the rotation matrix this way we can use the exponential map

\[R = e^{\hat{w}\theta} = I + \frac{\hat{\omega}}{\|\omega\|}\sin{(\|\omega\|\theta)} + \frac{\hat{\omega}^2}{\|\omega\|}\bigg(1 - \cos{((\|\omega\|\theta))}\bigg)\]where \(\hat{\omega}\) is defined as

\[\hat{\omega} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -\omega_3 & \omega_2\\ \omega_3 & 0 & -\omega_1\\ -\omega_2 & \omega_1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\in so(3) = \{S\in\mathbb{R}^{3\times3}\ |\ S^T = -S\}.\]This mapping is many-to-one, which says that there are many \(e^{\hat{w}\theta}\) corresponding to one \(R\), and for every \(R\in SO(3)\) we have more than one \(e^{\hat{w}\theta}\). To obtain \(\omega\) and \(\theta\) from \(R\) we have

\[\theta = \cos^{-1}\Big(\frac{\mathrm{trace}(R) - 1}{2}\Big)\ \mathrm{and}\ \omega = \frac{1}{2\sin\theta}\begin{bmatrix} r_{32} - r_{23}\\ r_{13} - r_{31}\\ r_{21} - r_{12} \end{bmatrix},\]we can see that the pair \((\theta, \omega)\) and \((2\pi - \theta, -\omega)\) can both obtain \(R\), thus makes this mapping many-to-one. Note that in the case where \(\theta = 0\) we can pick any arbitrary \(\omega\), which all makes \(R = I\).

Better understanding what rotation matrices represent

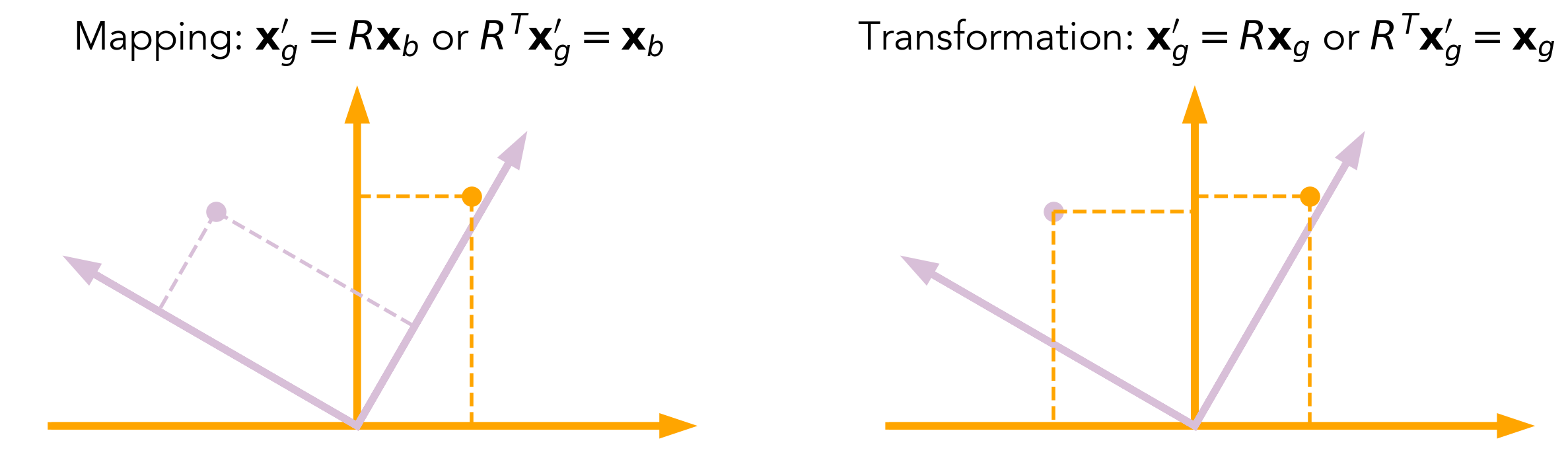

Rotation matrices can be seen as a mapping from describing a point in one coordinate frame to describing it in another coordinate frame. For the equation \(x_g^\prime = Rx_b\), we can see \(x_b\) as a point specified in a body frame \(b\) and \(x_g^\prime\) being the same point, however, specified in the coordinates of the global fixed frame \(g\). The rotation matrix \(R\) then serves as a mapping between these two representations.

Another way to see rotation matrices is to see it as an action, to rotate points in the same frame from one configuration to another. Using the equation \(x_g^\prime = Rx_g\), we can see \(x_g\) as the the point before applying the rotation \(R\) and \(x_g^\prime\) the point after applying rotation \(R\).

With these two views, we can now better understand how to represent rotations w.r.t the global fixed frame and the body frame. Now we ask, if sequentially applying two rotations \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) both specified in the body frame, where would the point end up in the global frame? Denote \(x_2\) as the final position in the global frame and \(x_0\) the initial position in the global frame, we want to find the rotation matrix between \(x_2\) and \(x_0\). First, we denote the initial position in the global frame as \(x_0^g\), where the superscript \(g\) denotes that this is represented in the global frame. After applying \(R_1\) we have

\[x_1^g = R_1x_0^g.\]One thing to note is that in the body frame the coordinates of the point is always the same, which is equal to \(x_0^g\). Thus we have

\[R_1^Tx_1^g = x_1^{1} = x_0^g,\]where the superscript 1 denotes the point represented in the body frame after rotation \(R_1\). If we see \(R_1\) as a mapping between points in the frame 1 and the global frame \(g\), we have the following relationship

\[R_1^Tx^g = x^{1}\ \mathrm{and}\ x^g = R_1x^{1}.\]Then we can see if we apply \(R_2\) which is w.r.t the frame \(b1\) we can have

\[x_2^{1} = R_2x_1^{1}\ \rightarrow\ R_2^Tx_2^{1} = x_2^{2} = x_1^{1} = x_0^g,\]similar to before this utilizes the fact that the coordinates of the point is kept constant in the current body frame. Finally, if we use \(R_1\) to map \(x_2^{1}\) to \(x_2^g\) we can have

\[R_1x_2^{1} = x_2^g,\]then we can have

\[x_2^{g} = R_1R_2x_0{g}.\]An interesting question would be after we get \(x_2^{g}\) if we rotate about the global frame using \(R_3\) and then rotate about the body frame using \(R_4\) what point will we end up at. If call the point after applying \(R_3\): \(x_3\), we can easily have

\[x_3^g = R_3x_2^g = R_3R_1R_2x_0^{g} = R_3R_1R_2x_3^{3},\]which again utilizes the fact that the body frame coordinates do not change \(x_3^{3} = x_2^{2} = x_1^{1} = x_0^g\). Also we obtain a mapping from the global frame and the body frame \(3\): \(x^g = R_3R_1R_2x^3\). Then if we apply \(R_4\), and get to point 4 we can have

\[x_4^{3} = R_4x_3^{3}\ \rightarrow\ R_4^Tx_4^{3} = x_3^{3} = x_4^{4} = x_0^g.\]To map \(x_4^{3}\) into the global frame we can have

\[R_3R_1R_2x_4^{3} = R_3R_1R_2R_4x_4^{4} = x_4^g\ \rightarrow\ R_4^TR_2^TR_1^TR_3^Tx_4^g = x_0^g\ \rightarrow\ x_4^g = R_3R_1R_2R_4x_0^g.\]Following this line of thought, I conjecture that we can completely decouple the rotations about the global frame and the body frame. I am pretty sure this is proved and shown somewhere, if anyone reading this has any information please let me know.

Rigid Motions in 3D

In this section I will talk about rigid motions which includes both translation and rotation. I will present three ways of describing such a motion, namely, homogeneous transformation, twist and screw motions, and we will see how these three descriptions are related.

Homogeneous Representations

Any rigid motion can be represented by a translation \(p\) and a rotation \(R\). If we perform such a transformation \(g(\cdot)\), we can relate the position before and after the transformation as

\[q^\prime = g(q) = p + Rq.\]And for a vector \(v\) we have \(g_*(v) = Rv\). This forms the special Euclidean group

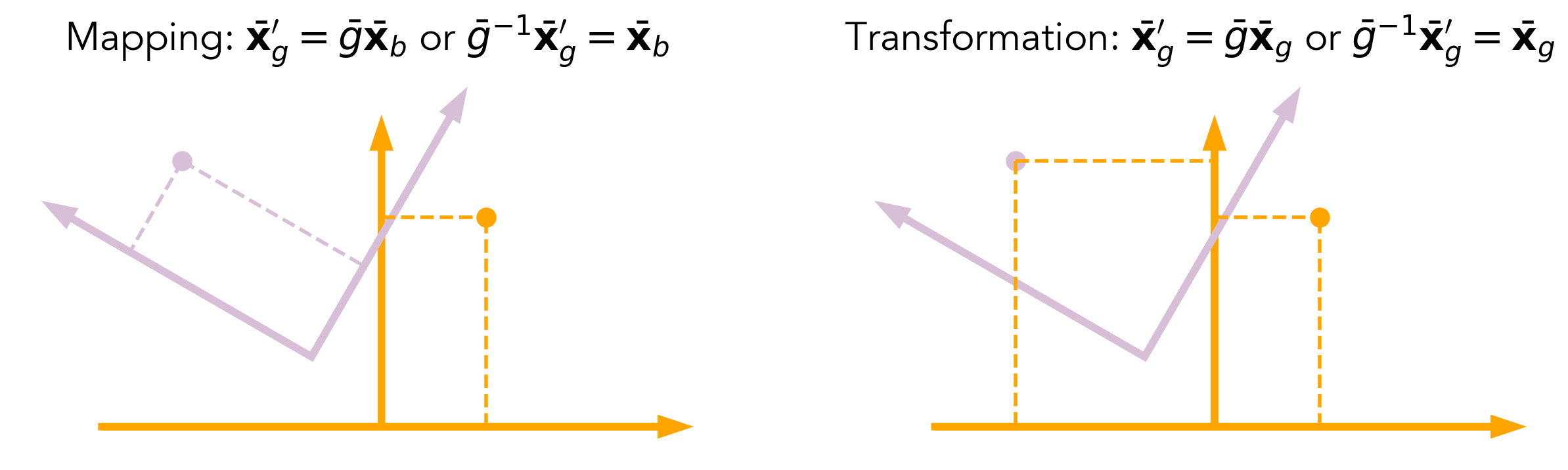

\[SE(3) = \{(p, R)\ |\ p\in\mathbb{R}^3, R\in SO(3)\} = \mathbb{R}^3\times SO(3).\]As before we can see this from two ways. If \(g(\cdot)\) is seen as an action then both \(q^\prime\) and \(q\) are measured in the same coordinate frame. If we see this as a mapping between frames, then \(q^\prime\) and \(q\) are measured in different frames. Later I will consolidate this using an example. Before that, I want to introduce the homogeneous representation of points and vectors. For a point \(p\) and vector \(v\) we can have their homogeneous representation as \(\bar{p} = \begin{bmatrix} p_1\\ p_2\\ p_3\\ 1 \end{bmatrix},\ \bar{v} = \begin{bmatrix} v_1\\ v_2\\ v_3\\ 0 \end{bmatrix},\)

here I would like to draw your attention to the last element, for points the last element is \(1\) and for vectors the last element is \(0\). The we can homogeneous representation of \(SE(3)\) as

\[\bar{g} = \begin{bmatrix} R & p\\ \mathbf{0} & 1 \end{bmatrix}.\]It is proved that \(SE(3)\) is a group, therefore, it satisfies the following properties

- If \(g_1, g_2\in SE(3)\), then \(g_1g_2\in SE(3)\).

- It has an identity element which is \(I_{4\times4}\).

-

There exists an inverse for \(g = (p, R)\in SE(3)\), defined as \(g^{-1} = (-R^Tp, R^T)\ \rightarrow\ \bar{g}^{-1} = \begin{bmatrix} R^T & -R^Tp\\ \mathbf{0} & 1 \end{bmatrix}.\)

- The composition rule \(\bar{g}_{ac} = \bar{g}_{ab}\bar{g}_{bc} = \begin{bmatrix} R_{ab}R_{bc} & R_{ab}p_{bc} + p_{ab}\\ \mathbf{0} & 1 \end{bmatrix}\) is associative.

Also we can prove that is a rigid transformation, which infers

- \(g\) preserves distance between points \(\|g(p) - g(q)\| = \|p - q\|\), for all \(p, q\in\mathbb{R}^3\).

- \(g\) preserves orientation between vectors \(g_*(v\times w) = g_*(v)\times g_*(w)\), for all \(v, w\in\mathbb{R}^3\).

Now I want to use an example to better understand the two views of this homogeneous representation. Consider rotating \(\theta\) about the vertical line going though point \((l_x, l_y, 0)\), how can we find the transformation \(g_{ab}\) such that \(x_g\) is the position of the point before and \(x_g^\prime\) is the position after, which are all represented in the global fixed frame. We can see this as two steps, a rotation \(R\) and a translation \(p\), the rotation is w.r.t the vertical line \((0, 0, 0)\) and the translation is from \((0, 0, 0)\) to \((l_x, l_y, 0)\). Denoting a point \(x\) with the coordinates in the body frame (light purple frame above) as \(x_b\), we define

\[x_b^1 = Rx_b.\]And after the translation we have

\[x_g^\prime = x_b^1 + p = Rx_b + p.\]Therefore we have

\[x_g^\prime = p + Rx_b\ \rightarrow\ \bar{g} = \begin{bmatrix} R & p\\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\theta & -\sin\theta & 0 & l_x\\ \sin\theta & \cos\theta & 0 & l_y\\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}.\]Also if we start at point \(x_g = x_b\), where \(x_g\) is measured in the global frame, this gives you a way to calculate the position after applying \(R\) and \(p\)

\[x_g^\prime = p + Rx_g.\]Twists

In the previous sections, we talked about how to rotate rigid bodies, however, all of them were rotating about an axis that passes through the global fixed frame, in this part in addition to introducing a more compact way of representing rigid body motion, I will also talk about how to rotate about axis that do not pass through the origin of the fixed frame. In the homogeneous coordinates we can write the pure rotation with unit velocity about axis \(\omega\in\mathbb{R}^3\)

\(\dot{p}(t) = \omega\times(p(t) - q)\) as \(\begin{bmatrix} \dot{p}\\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \hat{\omega} & -\omega\times q\\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} p\\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \hat{\xi}\begin{bmatrix} p\\ 1 \end{bmatrix}\ \longleftrightarrow \dot{\bar{p}} = \hat{\xi}\bar{p}.\)

Thus the solution \(\bar{p}(t) = \exp{(\hat{\xi}t)}\bar{p}(0)\) enables a mapping from the initial location to the location after \(t\) radians of rotation \(\exp{(\hat{\xi}t)}\). Note that here \(q\) is a point on the axis \(\omega\) given in the global coordinates. For pure translations we have

\[\hat{\xi} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & v\\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\]where \(v\) is a vector representing the translation velocity. We define twists as the group

\[\hat{\xi} \in se(3) := \{(v, \hat{\omega})\ |\ v\in\mathbb{R}^3, \hat{\omega}\in so(3)\} = \begin{bmatrix} \hat{\omega} & v\\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\in\mathbb{R}^{4\times4},\]with the twist coordinates \(\xi := (v,\ \omega)\). We can prove that for every member of \(se(3)\) we can find its corresponding element in \(SE(3)\) using an exponential mapping

\[\begin{align*} e^{\hat{\xi}\theta} &= \begin{bmatrix} I & v\theta\\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} & \omega = 0\\ e^{\hat{\xi}\theta} &= \begin{bmatrix} e^{\hat{\omega}\theta} & (I - e^{\hat{\omega}\theta})(\omega\times v) + \omega\omega^Tv\theta\\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} & \omega \neq 0. \end{align*}\]Also for every \(p, R\) we can find its corresponding twist \(\hat{\xi}\in se(3)\) and \(\theta\in\mathbb{R}\), for \(R = I\) we have

\[\begin{align*} \hat{\xi} &= \begin{bmatrix} 0 & p/\|p\|\\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} &\theta = \|p\|. \end{align*}\]If \(R \neq I\), then first we can solve for \(\hat{w}\) and \(\theta\) by solving \(e^{\hat{\omega}\theta} = R\), which was mentioned above. Then we can solve for \(v\)

\[v = \Big[(I - e^{\hat{\omega}\theta})\hat{\omega} + \omega\omega^T\theta\Big]^{-1}p.\]Note, here if we write \(p(\theta) = \exp{(\hat{\xi}\theta)}p(0)\), then \(p(\theta)\) and \(p(0)\) are specified in the same reference frame. If we want to specify \(p(0)\) in the body frame then we have

\[p(\theta) = \exp{(\hat{\xi}\theta)}g_{gb}(0)p^b(0)\]where \(g_{gb}\) gives the mapping between coordinates in the body and the global frame at \(t = 0\).

| Twist | Linear System | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| \(\dot{p}(t) = \omega\times(p(t) - q)\) | \(\dot{x}(t) = \omega(x(t) - O)\) | \(\xi = \begin{bmatrix}-\omega\times q\\ \omega\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}v\\ \omega\end{bmatrix}\), differential equations governing the movement |

| \(\dot{\bar{p}} = \hat{\xi}\bar{p}\) | \(\dot{x} = Ax\) | \(\hat{\xi} = \begin{bmatrix}\hat{\omega} & -\omega\times q\\ 0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\), differential equation in vector form |

| \(\bar{p}(t) = \exp{(\hat{\xi}t)}\bar{p}(0)\) | \(x(t) = \exp{(At)}x(0)\) | \(\exp{(\hat{\xi}t)} = \begin{bmatrix}e^{\hat{\omega}\theta} & (I - e^{\hat{\omega}\theta})(\omega\times v) + \omega\omega^Tv\theta\\ 0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\), analytic solution to differential equation. |

Screw Motion

Here we state Chasles’ Theorem: every rigid body motion can be realized by a rotation about an axis \(\omega\) combined with a translation parallel to that axis. We assume that the rotation is of \(\theta\) radians and the translation is of amount \(d\), also we can find a point on \(\omega\) and call it \(q\).

We can see that this movement resembles the movement of a screw. We can describe the screw movement using: pitch as \(h:=d/\theta\), the axis of the screw movement as

\[l = \{q + \lambda\omega\ |\ \lambda\in\mathbb{R}\}\]and a magnitude \(M = \theta\) when there is rotation and \(M = \infty\) when there is only translation.

For a given screw motion we can find its rigid transfomation as

\[\begin{align*} g &= \begin{bmatrix} e^{\hat{\omega}\theta} & (I - e^{\hat{\omega}\theta})q + h\theta\omega\\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} & \mathrm{with\ rotation}\\ g &= \begin{bmatrix} I & \theta v\\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} & \mathrm{pure\ translation} \end{align*}\]where \(v\) is the vector of translation. Additionally, when given a twist we can also find its corresponding screw, and given a screw we can find its corresponding twist.

Velocity of a Rigid Body

Rotational Velocity

First we define the spatial coordinate frame \(A\) which is fixed and the body coordinate frame \(B\) which is moving. If we define a point \(q_b\) in the body frame, and a rotation motion \(R_{ab}(t)\), then we can have the trajectory of the point in spatial coordinates as

\[q_a(t) = R_{ab}(t)q_b.\]By deriving that both \(R^{-1}\dot{R}\) and \(\dot{R}R^{-1}\) are skew symmetric matrices, we can get the angular velocity in both the spatial coordinate \(\hat{\omega}^s\) and the instantaneous body coordinate \(\hat{\omega}^b\) (since the body coordinate is changing due to rotation)

\[v_{q_a}(t) = \dot{R}_{ab}(t)q_b = \underbrace{\dot{R}_{ab}(t)R_{ab}^{-1}(t)}_{:=\ \hat{\omega}_{ab}^s}R_{ab}(t)q_b = \hat{\omega}_{ab}^sR_{ab}(t)q_b = \hat{\omega}_{ab}q_a.\]The instantaneous body angluar velocity is defined as seeing the spatial angular velocity vector in the body frame,

\[v_{q_b}(t) := R_{ab}^Tv_{q_a}(t)\ \ \ \ \hat{\omega}_{ab}^b = R_{ab}^{-1}\dot{R}_{ab}\]which is not the angluar velocity of the rigid body w.r.t the body frame, the latter is always zero.

Rigid Body Velocity

For a rigid motion plan \(g_{ab}(t)\in SE(3)\) we can get the spatial velocity as a twist \(\hat{V}_{ab}^s\in se(3)\)

\[\hat{V}_{ab}^s = \dot{g}_{ab}g_{ab}^{-1}\ \ \ \ V_{ab}^s = \begin{bmatrix} v_{ab}^s\\ \omega_{ab}^s \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} -\dot{R}_{ab}R_{ab}^Tp_{ab} + \dot{p}_{ab}\\ (\dot{R}_{ab}R_{ab}^T)^\vee \end{bmatrix}\]Thus the velocity of a point \(q_a\) can be found as

\[v_{q_a} = \hat{V}_{ab}^sq_a = \omega_{ab}^s\times q_a + v_{ab}^s.\]Here we can interpret \(\omega_{ab}^s\) as the instantaneous angular velocity of the body as viewed in the spatial frame and \(v_{ab}^s\) as the velocity of a (possibly imaginary) point on the rigid body which is traveling through the origin of the spatial frame at time \(t\). The body velocity is defined as

\[\hat{V}_{ab}^b = g_{ab}^{-1}\dot{g}_{ab}\ \ \ \ V_{ab}^b = \begin{bmatrix} v_{ab}^b\\ \omega_{ab}^b \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} R_{ab}^T\dot{p}_{ab}\\ (R_{ab}^T\dot{R}_{ab})^\vee \end{bmatrix}\]which for \(v_{ab}^b\) can be interpretted as the velocity of the origin of the body coordinate frame relative to the spatial frame, as viewed in the current body frame; for \(\omega_{ab}^b\) we can see it as the angular velocity of the coordinate frame, also as viewed in the current body frame. We can also define an adjoint transformation to relate the spatial and body velcoties

\[V_{ab}^s = \begin{bmatrix} v_{ab}^s\\ \omega_{ab}^s \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} R_{ab} & \hat{p}_{ab}R_{ab}\\ 0 & R_{ab} \omega_{ab}^b \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} v_{ab}^b\\ \omega_{ab}^b \end{bmatrix} = Ad_{g}V_{ab}^b.\]Coordinate Transformation

For three coordinate frames A, B and C, we can have the relationship between their spatial velocity as

\[V_{ac}^s = V_{ab}^s + Ad_{g_{ab}}V_{bc}^s\]similarly we can get the relationship between their body velocities as

\[V_{ac}^b = Ad_{g_{bc}^{-1}}V_{ab}^b + V_{bc}^b.\]This relationship can also be used to represent twists before and after applying a rigid motion

\[\xi^\prime = Ad_g\xi\ \ \mathrm{or}\ \ \hat{\xi}^\prime = g\hat{\xi}g^{-1}.\]Some additional properties include

\[\begin{align*} V_{ab}^{b} &= V_{ba}^{s}\\ V_{ab}^{b} &= -Ad_{g_{ba}}V_{ba}^{b} \end{align*}\]Wrenches

A wrench is defined as a force/moment pair \(F\in\mathbb{R}^6\)

\[F = \begin{bmatrix} f\\ \tau \end{bmatrix}.\]Given its dual nature with twist we have the relationship mapping wrenches between different coordinates systems as

\[F_c = Ad_{g_{bc}}^TF_b.\]And for the same wrench the instantaneous work is the same in both the spatial and body frame

\[\delta W = V^b\cdot F^b = V^s\cdot F^s,\]note that here \(\cdot\) represents the dot product.

Using Poinsot’s Theorem we can see every collection of wrenches applied to a rigid body is equivalent to a force applied along a fixed axis plus a torque about the same axis. Thus there exists a direct mapping between wrenches and screw motions.